Latest update February 22nd, 2026 12:38 AM

Latest News

- ExxonMobil eyeing new discovery at Goatfish-1 well

- $468M Bartica Water Treatment Plant commissioned

- Cuban security forces exit Venezuela as US pressure mounts

- Massy Gas Products among 10 vying to construct and operate cooking gas bottling company in Guyana

- When the Pipeline Is Ready but Development Is Not: Guyana’s Gas Moment Between Opportunity and Drift

When the Pipeline Is Ready but Development Is Not: Guyana’s Gas Moment Between Opportunity and Drift

Feb 22, 2026 Features / Columnists, News

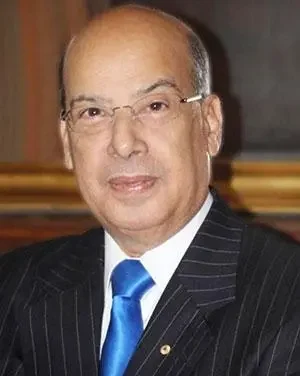

By Anthony Paul, Senior Energy and Strategy Advisor and former Director of Geology and Geophysics at the Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Energy.

(Kaieteur News) – For much of the past year, Guyana’s energy story has been told almost entirely through the language of speed.

Oil projects sanctioned ahead of schedule. Floating production vessels arriving one after another. Output climbing faster than even the most optimistic forecasts once imagined possible. The country has become, in record time, one of the world’s fastest-growing petroleum producers — a rare case where geology, capital and political will have aligned almost perfectly.

But at the recent Guyana Energy Conference and Supply Chain Expo, a different, quieter story emerged beneath the celebratory tone.

It was not about oil sprinting forward. It was about gas waiting.

When ExxonMobil executives stated that the offshore gas pipeline was built and ready to deliver, but that Guyana needed to advance industrial projects to maintain long-term demand, the message sounded technical. Even routine.

In reality, it was a strategic warning disguised as reassurance.

Because when steel is in the water and molecules are ready to move, but markets onshore are not yet constructed, gas development does not pause politely. It begins generating economic pressure, institutional strain, and political controversy.

This is the moment at which many gas provinces around the world quietly slide from promise into prolonged delay.

And it is precisely the moment where Guyana now stands.

Gas is not oil with different chemistry

Oil forgives sequencing mistakes. It can be stored, lifted by tanker, monetised project by project, and generates cash even when the rest of the system is incomplete.

Gas does not. Gas demands simultaneity.

Pipelines must land at the same time processing is built. Power plants must be ready when supply becomes available. Industrial users must exist before volumes ramp up. Contracts must align risk between State and investor. Institutions must be capable of steering complexity continuously.

If any single link lags, the whole value chain stalls — or worse, starts creating liabilities before it creates development.

This is why the “ready pipeline, waiting demand” framing matters so deeply. It marks the exact hinge where oil logic ends and gas logic begins.

History shows that countries that treat gas as merely the slower cousin of oil almost always underestimate how quickly delay becomes structural.

Dragon’s Forty-Year Lesson: Gas Does Not Fail — Alignment Does

The Dragon field offshore Venezuela was not a geological disappointment. Discovered in the late 1970s, appraised in the 1980s, engineered in the 1990s, drilled and partially built in the 2000s, and nearly piped to shore by the mid‑2010s, the gas remained exactly where it had always been.

What kept changing was everything around it.

Markets shifted. Capital cycles tightened. Institutions were reorganised. Geopolitics intervened. Development strategies were repeatedly reinvented.

Dragon did not wait because gas was hard. It waited because integrated alignment never held long enough.

Only when Trinidad and Tobago’s existing gas‑hungry industrial system finally intersected with Venezuela’s stranded abundance did monetisation become inevitable.

Not through new discovery. Through belated architectural coherence.

The Global Pattern Guyana Is Quietly Entering

Guyana is not Venezuela. Its governance context is different. Its geopolitics are different. Its oil revenues are already flowing.

But the structural physics of gas do not change with optimism.

Across the world, major gas provinces follow a familiar rhythm: oil accelerates naturally, gas only moves when institutions force alignment.

In Mozambique, world-class discoveries stalled for years as security risk, financing cycles and LNG megaproject complexity collided.

In Tanzania, negotiations over a single massive export project have stretched over a decade, turning gas perpetually into “next phase development.”

In Namibia, high gas content has complicated oil-first strategies and delayed final investment decisions.

In Suriname, early discoveries now face the same sequencing choices between rapid oil monetisation and slower gas architecture.

Everywhere the lesson is the same: Oil accelerates naturally. Gas only moves when institutions force alignment.

Left to market timing and portfolio priorities alone, gas almost always drifts.

Guyana’s Quiet Strength — and Its Quiet Risk

To Guyana’s credit, transparency has been a defining feature of its petroleum management so far. Data has been published. Costs discussed publicly. Contracts debated. Independent experts allowed space to scrutinise assumptions.

This is not cosmetic. It is a genuine institutional asset.

But transparency alone does not build markets.

Upstream delivery is no longer the binding constraint. Downstream architecture now is – power systems, industrial demand, tariff frameworks, commercial risk allocation.

These sit squarely within sovereign responsibility.

The Trinidad & Tobago Misread

Much regional commentary focuses on Trinidad and Tobago’s recent gas decline – falling production, ageing fields, underutilised LNG trains, declining government revenue, slowing economy. What is often forgotten is that Trinidad’s early gas build‑out phase was one of the most successful examples of small‑state industrial gas strategy anywhere in the developing world.

The State did not wait for export markets to mature. It deliberately constructed domestic sinks for gas: power generation, ammonia and fertiliser, methanol, steel and downstream manufacturing. Gas was treated as a development instrument, not a by‑product.

Industrial estates were built around gas availability. Contracts anchored long-term demand. Midstream institutions coordinated sequencing, shared infrastructure and services

Trinidad’s later challenges stem largely from upstream decline and policy inertia, not from failure of the original gas‑industrialisation model.

For Guyana and Suriname to focus only on Trinidad’s present difficulties, and allow sentiment to obscure what once worked extraordinarily well, would be to discard one of the region’s most valuable institutional case studies.

The Sophisticated Investor Problem

Another reality sits quietly beneath Guyana’s success story.

The upstream partner driving development is among the most technically sophisticated and commercially disciplined energy companies on the planet.

Its project sequencing, capital allocation and contract design are optimised relentlessly for global portfolio performance.

That is not a criticism. It is its mandate.

But when a young petroleum state’s technical and commercial capacity is still evolving, the risk is not bad faith – it is asymmetry.

Decisions made quickly offshore can become extremely difficult to unwind onshore once steel is laid, costs are sunk and contracts activate.

This is precisely why gas requires stronger, earlier institutional steering than oil.

Oil can be course-corrected field by field. Gas locks systems together for decades.

The Moment Before Drift

Guyana now stands at a rare advantage point. The pipeline exists. The gas volumes are real. Oil revenues provide fiscal breathing space. Public scrutiny is active.

This is the window when gas architecture can still be deliberately designed rather than inherited by default.

The core questions are institutional, not geological.

- Who is the long-term off-taker — and on what risk terms?

- What triggers take-or-pay obligations?

- How are cost recovery optics managed transparently?

- What industrial demand will anchor volumes beyond power generation?

- How is sequencing enforced across ministries, regulators and investors?

Without clear answers, delay does not remain neutral. It becomes expensive, politicised, and eventually structural.

Gas as Development Vehicle — or as Deferred Promise

Nothing in Guyana’s story suggests failure. Quite the opposite.

But every delayed gas province once stood exactly where Guyana stands now: confident in reserves, optimistic about infrastructure, assuming markets would naturally follow.

They rarely did without forceful institutional design.

Dragon waited forty years not because gas was difficult, but because alignment was never held long enough.

Trinidad’s early success came precisely because alignment was engineered deliberately.

Guyana now has the chance to choose which model it follows.

Not in speeches. In sequencing. In contract design. In market construction. In institutional capacity.

Gas will not automatically become a development engine simply because it exists offshore. But with disciplined architecture, it can transform power costs, industrial depth, employment and economic resilience for generations.

This is the moment before drift.

And history suggests that what happens next depends far less on geology, and far more on governance.

Photo saved as Antony Paul

Discover more from Kaieteur News

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Similar Articles

Listen to the The Glenn Lall Show

Follow on Tik Tok @Glennlall

Your children are starving, and you giving away their food to an already fat pussycat.

Sports

Feb 22, 2026

Kaieteur Sports – As Petra Organisation ramps up preparations to host the quarterfinal stage of the ongoing Modec Tertiary Football Tournament, the tournament received another major boost with...Features/Columnists

Feb 22, 2026

(Kaieteur News) – There is an old saying that sometimes we build our own trap and then complain when we are caught in it. Today, the leadership of the PPP seems to be in just such a bind — a bind of its own making. For years, the party has claimed that it practices internal democracy....Sir. Ronald Sanders

Feb 22, 2026

By Sir Ronald Sanders (Kaieteur News) – If U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio accepts the invitation to attend the CARICOM Heads of Government meeting in St Kitts and Nevis from 25 to 27 February, his presence should be treated as consequential. It would offer an opportunity to recalibrate the...The GHK Lall Column

Feb 22, 2026

Hard Truths by GHK Lall (Kaieteur News) – I term it a team effort, 100% proof. Strong Cajun bourbon (or moonshine) to settle the spirit. US Ambassador, Excellency Nicole D. Theriot appointed herself emcee, did the honors. The US is 100% committed to get the Mohameds stop-and-start...Publisher’s Note

Freedom of speech is our core value at Kaieteur News. If the letter/e-mail you sent was not published, and you believe that its contents were not libellous, let us know, please contact us by phone or email.

Feel free to send us your comments and/or criticisms.

Contact: 624-6456; 225-8452; 225-8458; 225-8463; 225-8465; 225-8473 or 225-8491.

Or by Email: glennlall2000@gmail.com / kaieteurnews@yahoo.com